Genius on Sitting Down to Read King Lear Again

22 Jan 1818: Reading King Lear & Changing, Ripening Intellectual Powers; Keats's Reality Principle

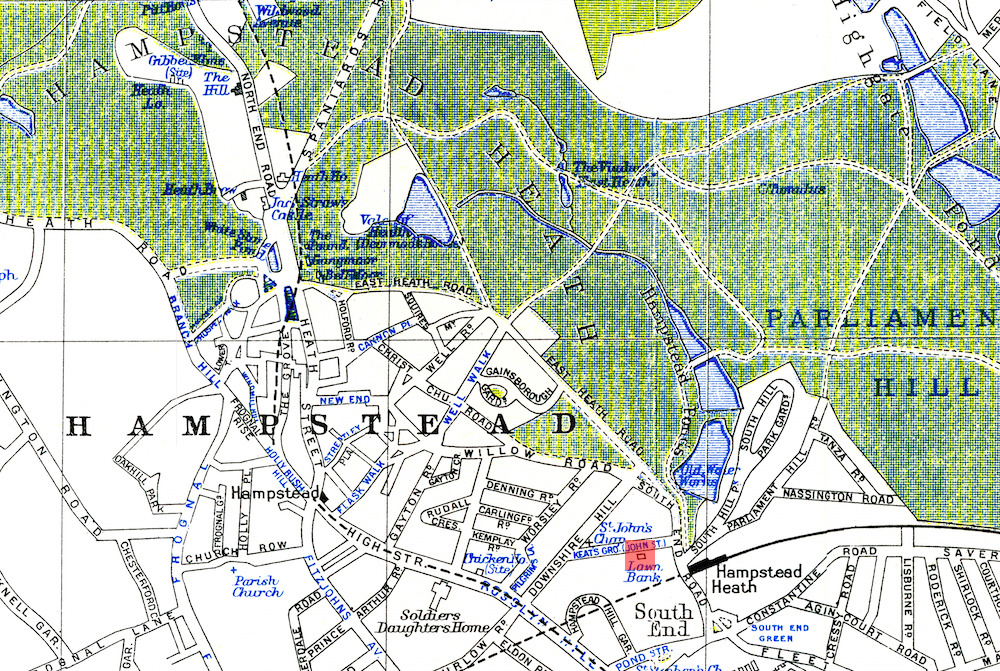

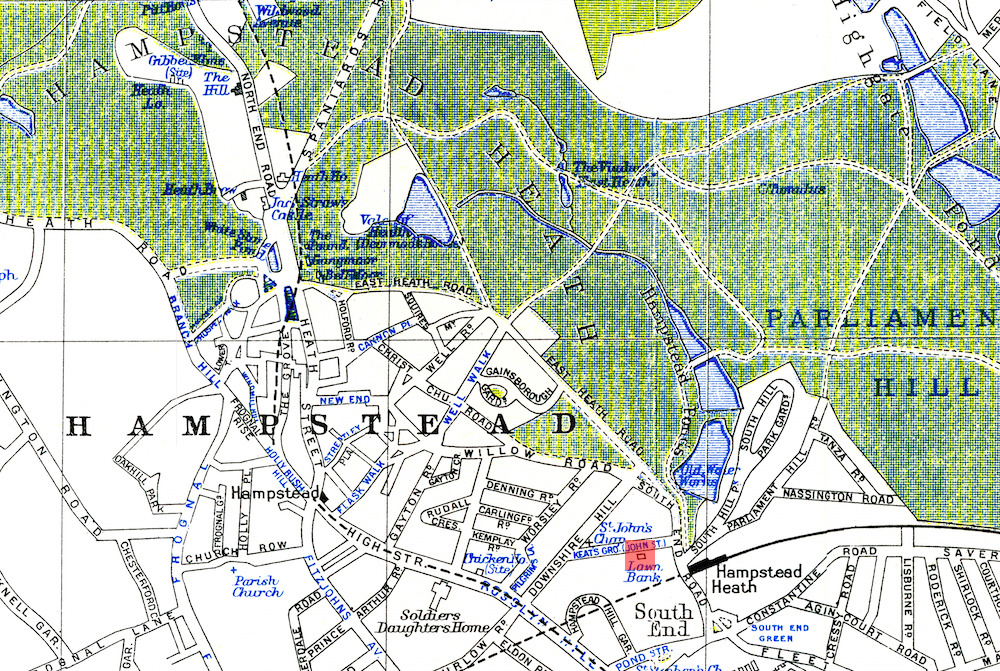

1 Well Walk, Hampstead

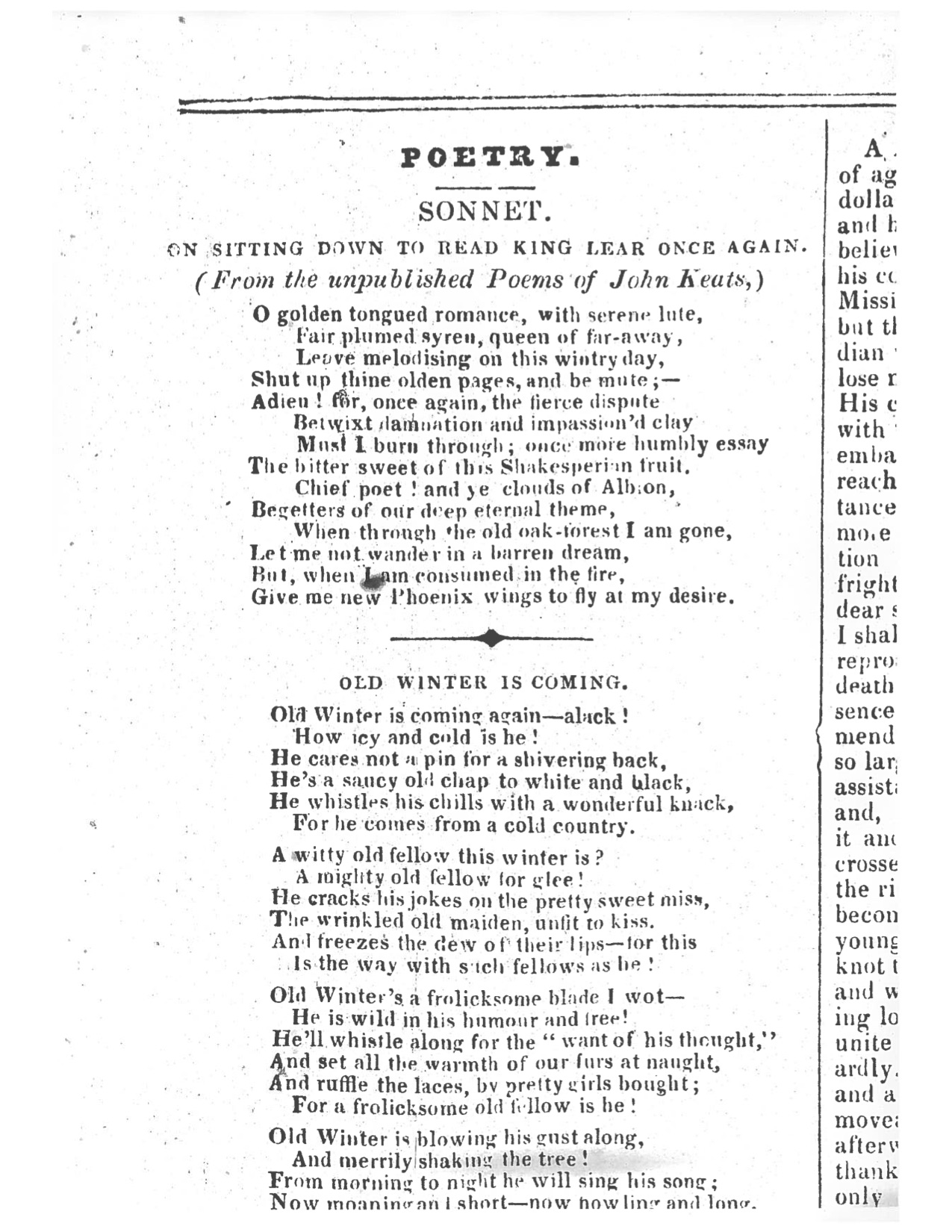

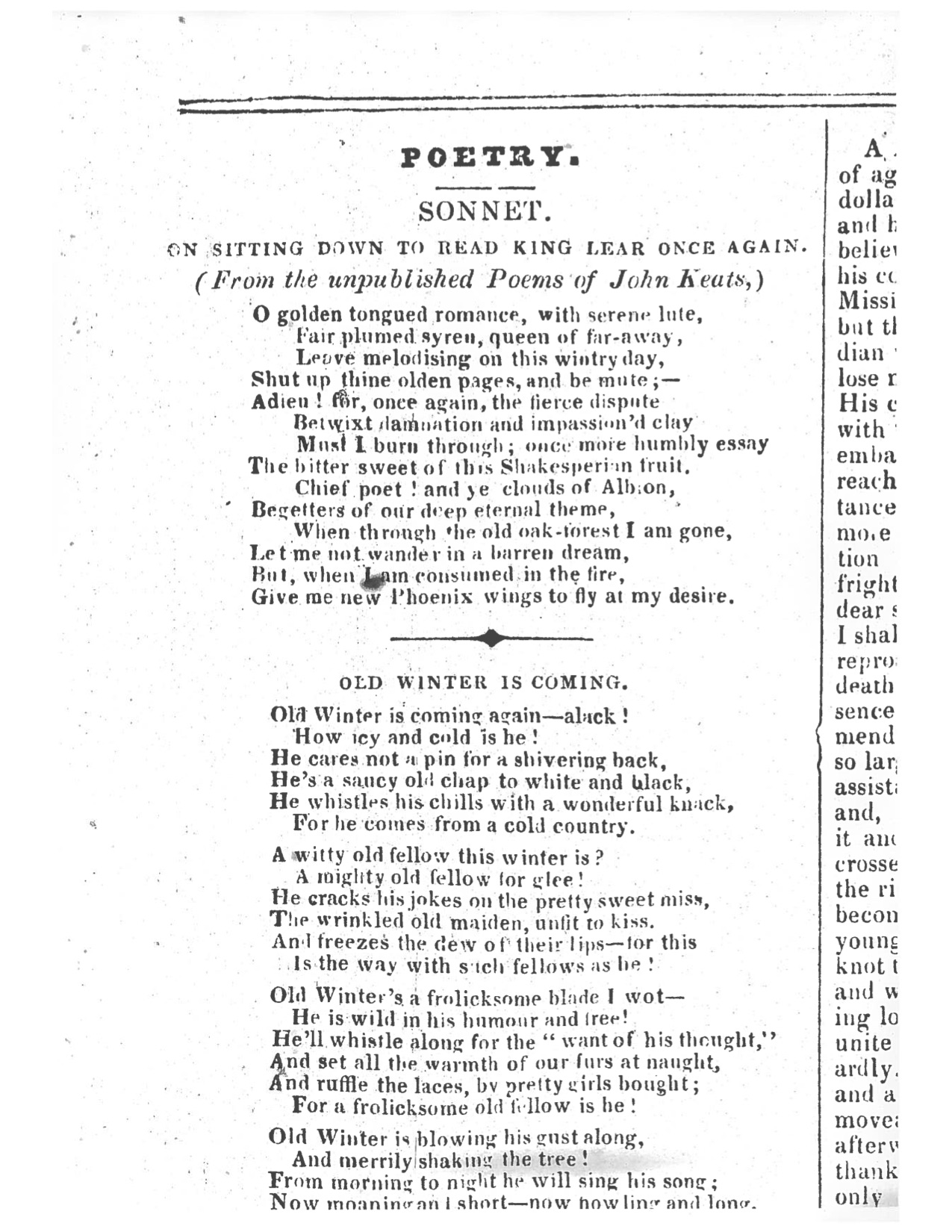

Keats has Shakespeare's King Lear on his mind, and forth with Hamlet, it remains for Keats the most strong poetic measure of depth and complexity. Today Keats writes a sonnet about the play—Keats remains overwhelmed past the greatness of the thing

(23 January 1818, to Bailey).

In gauging his own progress, and with King Lear in mind, Keats writes that at that place has been a niggling change […] in my intellect lately,

and that Cipher is effectively for the purposes of great productions, than a very gradual ripening of the intellectual powers

(messages, 23, 24 Jan). The proffer, of class, is that Keats is himself feeling or hopes to experience such a ripening,

and this (as a metaphor of organic maturation) is of import in his self-conception of poetic progress. His long trial-of-invention poem, the 4,050-line Endymion, will, within two months, finally exist behind him. He has just shown the opening book of Endymion to Leigh Hunt, who sees himself as Keats's mentor; and Hunt, in skimming it, says it has non much merit,

and that the conversation betwixt the two main characters is unnatural & too high-flown.

Hunt also adds that they would not speak similar his own characters in his own verse form, The Story of Rimini. Keats finds Hunt's comments wrong, not to mention both petty and pompous. More reason for Keats to motility even farther from Hunt's sway of influence, though there is some truth in saying that Huntian tones practice inhabit Keats's rambling verse form (and a fair corporeality of his early verse).

Although Keats's sonnet on King Lear is about both Shakespeare'southward greatness as well equally his own aspirations for greatness, On Sitting Downwardly to Read Rex Lear Once Once more itself is not especially great. Keats resorts to a couple of clichéd, rhapsodic phrases—O golden-tongued Romance, with serene lute!

—on his manner to call upon The bitter-sweet of the Shakespearean fruit

to help his wings to fly at my desire

—his want

to exist an enduring poet, that is. This is Keats's almost persistent—and dead-stop—topic, especially in its ties to poetic fame. Only there is at least something more deliberate and of import in the sonnet, something that expresses a specific and deliberate mandate for this poetic progress: to say good-bye to melodizing

romance while welcoming the Shakespearean deep eternal theme

of sadness and pain, of immortality and death. This welcoming is significant enough: beginning in his earliest piece of work, Spenserian impulses especially run through Keats's diction and poetic mannerisms; but equally he matures, the charms of chivalric beauty and elfin ambiance increasingly limit his more intense and comprehensive goals, and after Endymion they begin to noticeably drop off. The allegorical-mythical romance of Endymion holds upwardly rather than advances Keats'south progress—merely at to the lowest degree he learns what he shouldn't exercise again. Every bit he suggests in the overly apologetic preface to his too-long verse form, he pledges that if and when he returns to a Greek mythology, information technology volition be with some poetic maturity.

At the finish of Jan, Keats writes a kind of follow-up verse form—When I accept fears—to the Lear sonnet. Information technology may be his first Shakespearean sonnet. Keats fears that time will compromise his teeming brain

and poetic aspirations, and therefore it returns to Keats'south thus-far longest running bailiwick: the desire to exist inspired and to write inspirational verse, and how he might reach these goals. This fourth dimension, however, the sonnet is personal however less affected. Although the verse form Byronically self-dramatizes his gloomy fears and condition—I stand alone

—it remains more controlled in attitude and purposefully dramatic in its rhetoric. Merely what we are commencement to see more than and more clearly is that Keats wants to, every bit it were, detect some new commencement to his poetic pursuits. Nosotros might venture, so, that Keats is working toward a third phase of poetic development (the first revolving around his showtime collection, the 1817 volume; the second revolving effectually the completion of Endymion); information technology volition be his last, and will marker a leap forward in his prowess equally a poet. How strongly does Keats feel he has a new phase to move to? The side by side day, 23 Jan, in a letter to his close friend Benjamin Robert Haydon, Keats deliberately anticipates leaving behind the sentimental cast

of Endymion so that he tin can motion on to his Hyperion project, which will be written in a more than naked and Grecian manner

and be more undeviating

in its intention and narrative. In brusk, Keats is self-consciously is working toward less ineffectual poetic decorum, more direct story-telling, and a more elevated style. This bodes well.

Keats besides likely writes another poem in January that somewhat similarly signals his desire to experience absorbed past the thoughts of before writers. The lively Lines on the Mermaid Tavern once again expresses Keats's desire for alignment with Souls of poets expressionless and gone.

The mythology revolving around the Mermaid Tavern (where Keats spends at least one evening effectually this time) is that famous Elizabethan writers gathered there equally a lodge to accept drink, converse, contend, and exhibit wit. Maybe something volition rub off on him.

As suggested, King Lear, with its speculative, intensive depths, remains perhaps the most powerful single creative work for Keats. Nosotros know from Keats's heavily marked up copy of William Hazlitt's recently published Characters of Shakespeare'southward Plays that he is fully captivated with trying to understand King Lear's imaginative portrayal of and control over tensions, passions, conflicts, and oppositions. This becomes Keats'south existent work at this time, and, as he copies and revises Endymion, its shortcomings—indeed, its relative haphazard quality—become very clear. Keats recognizes that, to be a significant poet, he needs to embrace depths and complexities in feeling and thought, and in composed and disinterested nevertheless imaginative means; subjects are to be finely pushed up against excess without crossing over into sentimentality. Keats is coming to run across that life, feelings, and thought are necessarily at the call of change, incertitude, and irresolution; imaginatively embracing and representing this realization and these topics is critical, and something we might call Keats's reality principle—and, once more, they volition be present in his best work to come.

Also, and related to this pursuit, Keats about this time begins to realize that he needs to—and tin can—profitably engage with the achievement of Milton and Wordsworth, alongside Shakespeare. For Keats, Milton's verse unshakeably holds its subjects, thus turning moving description into stilled drama. Wordsworth's verse pursues deep, tranquility truths beyond both joy and fearfulness—a region that Wordsworth seminally points to equally also deep for tears

(from Wordsworth'south Immortality Ode). Equally significant, Keats begins to know what he will not emulate: aspects of Milton's fashion and Wordsworth subjectively channeled vision. Withal, in about a year-and-a-half, just as Keats writes his very all-time poetry, he can say, Shakespeare and the [Milton's] Paradise Lost every day get greater wonders to me

(letters, fourteen Aug 1819), and we witness Keats's recognition of the importance of how Wordsworth tin can think into the human eye

(letters, three May 1818). We know, so, that Keats'southward deliberate study of these figures in particular greatly propels his own work. [For more on Milton and Wordsworth, run into 5 May 1818.]

That William Hazlitt is both a friend and a disquisitional influence is not casual: Keats at this juncture reads Hazlitt's critical piece of work, attends his lecture series on literature, and socializes with him. They no doubt talk most the qualities of poetic stature, which ties into Keats's interest in how the thespian (and living legend) Edmund Kean embodies Shakespeare's words—a quality to which Hazlitt is greatly attuned, and something he has written about. This shapes Keats's idea about how poetic phonation assimilates and represents meaning. Keats is intrigued by Kean's ability to physically evoke Shakespeare's actual words (his concrete text, in event): the grapheme becomes the words, and words become the character. That is, Kean's acting embodies words as much as persona. This anticipates Keats's own theory of the camelion poet

(letters, 27 Oct 1818); Kean is, in issue, the camelion actor, bold, every bit it were, the changing shapes and colours of Shakespeare'due south words. Keats'south ultimate appetite, expressed at the meridian of his powers, is to make every bit corking a revolution in modern dramatic writing as Kean has done in acting

(messages, 14 Aug 1819); this never happens, though—who knows?—if Keats would accept lived beyond xx-v years, his remarkable poetic gifts may well have been translated into drama.

At this moment, Keats is somewhat defensive about his poetry in light of Hunt's somewhat patronizing comments nigh Endymion. The suggestion is perhaps not so much that he does not trust Chase's comments, but that Chase makes them in the get-go identify, which suggests Chase'southward sense of ownership over Keats's poetic progress. There may be something that Keats might non want to direct admit: that aspects of Hunt'south poetic style (which is overly affected, at times, prettified, sometimes stylistically flippant) lurk in his own poetry. But, as suggested above, Keats knows this, and he is very adamant to move frontwards in his ain style and in his own terms, fortified by his written report, his poetics, and the support of his closest friends.

The next day (23 Jan) Keats begins to set up Book Two of Endymion for the printing, and his brother Tom'south wellness is not expert. Every bit usual, Keats'southward finances are uneven at best and precarious at worst.

Source: https://johnkeats.uvic.ca/1818-01-22.html

Post a Comment for "Genius on Sitting Down to Read King Lear Again"